Copyright © – 2007 – by Steven McFadden

After walking 3,500 miles from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and arriving somewhat south of the place native people know as the Western Gate of Turtle Island, a band of pilgrims encountered the poet Gary Snyder on the last night of January, 1996. We had been walking toward this Western Gate for eight months, so we were paying attention to the portents.

With several other pilgrims, I heard Snyder speak that night at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He said that when he considered modern man’s relationship to the earth, he felt it lacked a conscious spiritual connection. “The fire of catastrophe,” said he, “has burnt out all.”

Snyder revealed himself as one the many elders we had set out to find on our prophetic quest across the back of North America. He’d sounded a steady incantation for decades on behalf of the earth, his words finally reaching our pilgrim ears at the end of our epic walk specifically in quest of sacred places and steadying voices.

Snyder revealed himself as one the many elders we had set out to find on our prophetic quest across the back of North America. He’d sounded a steady incantation for decades on behalf of the earth, his words finally reaching our pilgrim ears at the end of our epic walk specifically in quest of sacred places and steadying voices.

As it happens, poet Snyder won a Pulitzer Prize for authoring the collection, Turtle Island. He summoned his title from the creation stories native to our North American continent – the old, old name.

That night in Santa Barbara, Snyder said that ,as he saw things now on Turtle Island, people have organized themselves by race, gender, belief systems, and so forth. But we have not yet organized ourselves by ecosystems – the actual places where we live, and the actual resources native to these places.

“Nature is no social construction,” Snyder said. “The land sees no colors.”

Using high language and artful rhythm, Snyder told us that when we come to comprehend this, it will help us all to finally and truly become Native American in the full spiritual sense that embraces all the land and all the people, the plants and the animals.

Through hearing the poet’s lyric, I came once again to a basic realization about why we had walked, and what we – a multicultural, all-faiths band of pilgrims — hoped to accomplish with our procession on foot across North America to meet some of the contemporary elders of our land. We were striving to help establish the kind of authentic spiritual connection with the earth that Snyder invoked with his words.

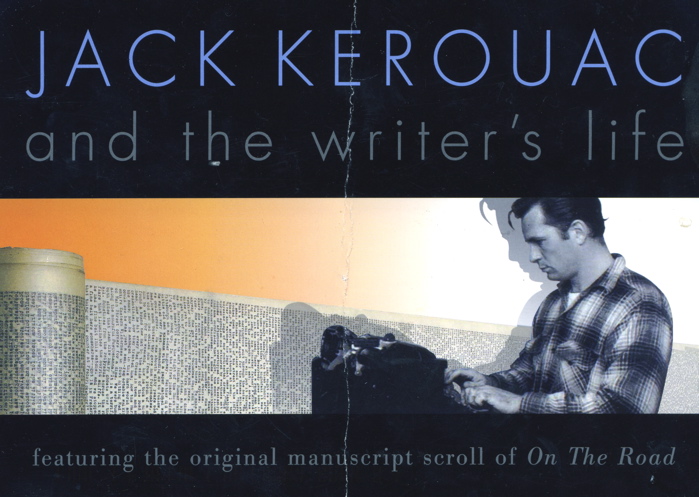

Eleven years after the end of the walk, in 2007 shortly after I finished writing the story of our walk in the form of an epic nonfiction saga (Odyssey of the 8th Fire), Gary Snyder reappeared. This time the poet came to Santa Fe to speak about his late compatriot, Jack Kerouac, the writer who crafted an undulating, enduring paean to America and freedom with his novel On the Road (1957)

Snyder was invited to Santa Fe by the Museum of New Mexico and the Palace of the Governors. They asked him to speak as a complement to their exhibit of Kerouac’s work, including the original, continuous and amazing 120-foot teletype scroll that Kerouac used for writing On the Road – a novelized account of open, mad, freedom-expressing rushes across the back of Turtle Island in the late 1940s and early 1950s, with beauty to behold and creative souls to encounter.

Poster for the Santa Fe events.

On stage in downtown Santa Fe at the packed Lensic theater, Snyder told the audience that back in 1956 he had use of a cabin near Homestead Valley, just north of San Francisco. It was a rude structure, lacking glass for the windows. In this country abode, Kerouac moved in with him for 5-6 weeks – a place to crash.

Very much in command as he stood center stage, Snyder spoke directly of his friend Jack Kerouac as a man who was well intentioned, sweet, playful, sometimes goofy, non-judgmental, and imbued with the spirit of compassion. He said Kerouac was keenly intelligent, well read, and had a mind for words. One of Kerouac’s prime spiritual gifts, the poet said, was his ability to confront the immediacy of his imagination.

I listened to Snyder attentively. I wanted to understand more. In preparing to write the nonfiction saga of our long walk across Turtle Island — Odyssey of the 8th Fire — I’d been informed by books telling of our human journey: Homer’s Odyssey, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Steinbeck’s Travels with Charlie, William Least Heat Moon’s Blue Highways, Cervantes’ Don Quixote, and Paolo Cohelo’sThe Pilgrimage. Inevitably, Kerouac’s On the Road also touched me with its entraining cross-America accounts of reaching outward, inward, downward, upward.

The miles that Kerouac’s Beatniks traveled in cars and buses and by hitchhiking, we odyssey pilgrims later traversed on foot – as if that were an era wanting speed to break free of bonds, and the era of our walk a time to slow down, to take measure of the vast, multi-faceted spiritual landscape sprawled out before us, to proceed across it at a more deliberate pace.

With the overarching thrust of their works, Kerouac and Snyder were among a multitude of inspirations for me. In Odyssey of the 8th Fire, the actual Turtle Island emerges from the depths of North America with immediacy and relevancy. Spiritual elders of North America step forward by the dozens to share teachings of our land.

The spontaneous, howling, Beat pilgrims Jack Kerouac wrote about were, in one conception, on the road for truth, freedom, and spiritual realization advancing in their time and place. Our on-the-road walking quest some fifty years later was, in part, a natural extension and evolution of this fundamental quest, and also a part of the overall, amazing, grand, hope-lifting odyssey of all of us: multicolored, multi-faith masses of people over centuries of time striving awkwardly, unceasingly to establish a conscious, realized connection with the spirit of this beautiful land that we might finally be truly at home here on Turtle Island, and that the land and water and air might cleanly support our children and grandchildren in health and freedom.

We odyssey walkers stretched out our legs and strode toward what we felt could help. We did what we could. We walked to a great many of the holy sites of Turtle Island, and there enacted ceremony for all of the sacred hoop of life on Turtle Island, respecting all spiritual traditions and all colors of humanity – as had been the agreed-upon philosophy of our pilgrimage band, some 40 or more multicultural souls.

As it happened, as it happens. Circumstances impend. Roadways exist. Poets sing.

END

Resources

Jack Kerouac – On the Road

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Road

Gary Snyder

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gary_Snyder

Palace of the Governors, Santa Fe, NM, USA

http://www.palaceofthegovernors.org/

Odyssey of the 8th Fire

http://www.8thfire.net

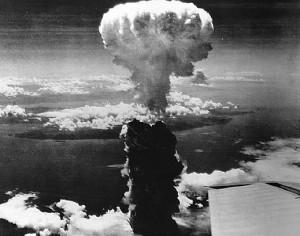

The fire that was ignited 57 years ago on August 6, 1945 when the Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, was ceremonially extinguished by a band of pilgrims May 27, 2002 at Big Mountain on Black Mesa in Arizona, in a high desert range sweet with the smell of sagebrush.

The fire that was ignited 57 years ago on August 6, 1945 when the Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, was ceremonially extinguished by a band of pilgrims May 27, 2002 at Big Mountain on Black Mesa in Arizona, in a high desert range sweet with the smell of sagebrush.

The assault on the material resources of Black Mesa continues. Peabody Coal Co. is planning on expanding operations by opening a new mine, which will ultimately infringe upon Big Mountain itself.

The assault on the material resources of Black Mesa continues. Peabody Coal Co. is planning on expanding operations by opening a new mine, which will ultimately infringe upon Big Mountain itself.

The Hiroshima Flame Interfaith Pilgrimage had its origins in the year 2000 under the inspiration of Tom Dostou while he was in Japan. At that time he was entrusted with a spark of the Hiroshima Flame (the source flame remains burning in Japan). Tom conceived the vision of returning the flame to where it had come from — not as a protest, but as a necessary deed of spiritual redemption, because not only the people of Hiroshima had died, but also many native peoples were poisoned by the uranium dug up, without spiritual permission, on their lands.

The Hiroshima Flame Interfaith Pilgrimage had its origins in the year 2000 under the inspiration of Tom Dostou while he was in Japan. At that time he was entrusted with a spark of the Hiroshima Flame (the source flame remains burning in Japan). Tom conceived the vision of returning the flame to where it had come from — not as a protest, but as a necessary deed of spiritual redemption, because not only the people of Hiroshima had died, but also many native peoples were poisoned by the uranium dug up, without spiritual permission, on their lands.

The flame, flickering in a lantern borne by pilgrims on foot, was largely unrecognized and unacknowledged in Los Alamos. Still, the pilgrims completed the work of spiritual redemption they had come to accomplish, and then they walked on toward the East, planning to arrive in New York City on May 12, 2002. Their visit to this place of fire is of marked spiritual significance.

The flame, flickering in a lantern borne by pilgrims on foot, was largely unrecognized and unacknowledged in Los Alamos. Still, the pilgrims completed the work of spiritual redemption they had come to accomplish, and then they walked on toward the East, planning to arrive in New York City on May 12, 2002. Their visit to this place of fire is of marked spiritual significance. In the beginning, it is said, the four nations lived together as one and shared their gifts. Then came a time when it was necessary for spiritual growth that the Four Nations disperse to the Four Directions and live apart. Over time they could develop as human beings and master the mysteries of their element for good or ill, according to their free will. Earth, air, fire and water — the peoples went apart.

In the beginning, it is said, the four nations lived together as one and shared their gifts. Then came a time when it was necessary for spiritual growth that the Four Nations disperse to the Four Directions and live apart. Over time they could develop as human beings and master the mysteries of their element for good or ill, according to their free will. Earth, air, fire and water — the peoples went apart.

The flame the pilgrims carry was ignited 57 years ago and has been tended with prayer ever since. In1945, after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, a man named Tatsuo Yamamoto walked into the ruins of the city to look for friends and family. In shock and anger, he collected some of the embers still smoldering from the bomb and carried them home.

The flame the pilgrims carry was ignited 57 years ago and has been tended with prayer ever since. In1945, after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, a man named Tatsuo Yamamoto walked into the ruins of the city to look for friends and family. In shock and anger, he collected some of the embers still smoldering from the bomb and carried them home. The nuclear bomb is an ultimate expression of materialism. When the atomic scientists of Los Alamos took the secret of the atom — the fundamental particle of matter — and developed it into a weapon of mass destruction, they unleashed a scathing, wrathful demon of fire rather than a higher angel of warmth and illumination.

The nuclear bomb is an ultimate expression of materialism. When the atomic scientists of Los Alamos took the secret of the atom — the fundamental particle of matter — and developed it into a weapon of mass destruction, they unleashed a scathing, wrathful demon of fire rather than a higher angel of warmth and illumination.

The glyph was carved into the rock face of the outcropping thousands of years ago by the indigenous Pueblo peoples, whose descendents still live nearby. There are such petroglyphs all over North America, serving as signs and signals of importance to native peoples.

The glyph was carved into the rock face of the outcropping thousands of years ago by the indigenous Pueblo peoples, whose descendents still live nearby. There are such petroglyphs all over North America, serving as signs and signals of importance to native peoples. From the place of Avanyu, the walkers proceeded — drumming and chanting each step — about seven miles to Tsankawi, a prehistoric site that is now part of Bandelier National Monument. Tsankawi is a spectacular place high on a mesa overlooking the Jemez Mountains to the West and the Sangre de Christo Mountains to the East.

From the place of Avanyu, the walkers proceeded — drumming and chanting each step — about seven miles to Tsankawi, a prehistoric site that is now part of Bandelier National Monument. Tsankawi is a spectacular place high on a mesa overlooking the Jemez Mountains to the West and the Sangre de Christo Mountains to the East. The wind people, the messengers, brought the flame home to its point of origin, having purified it with their chants, prayers and incense. They offered it to the people of the city without rancor, recrimination, or challenge. They offered the flame with understanding and hope. And then they walked on.

The wind people, the messengers, brought the flame home to its point of origin, having purified it with their chants, prayers and incense. They offered it to the people of the city without rancor, recrimination, or challenge. They offered the flame with understanding and hope. And then they walked on. Also on that day, to sound an alarm about the rapidly growing danger of a nuclear conflagration, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved their famous Doomsday Clock forward two minutes closer to midnight. The scientists wanted to highlight the dramatically mounting dangers of political instability, the wide availability of nuclear materials, terrorism, and the aggressive unilateral stance of the US government.

Also on that day, to sound an alarm about the rapidly growing danger of a nuclear conflagration, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved their famous Doomsday Clock forward two minutes closer to midnight. The scientists wanted to highlight the dramatically mounting dangers of political instability, the wide availability of nuclear materials, terrorism, and the aggressive unilateral stance of the US government. As a journalist, I’m the author of a range of

As a journalist, I’m the author of a range of  A

A