Don Bustos of Santa Cruz Farm (author photo)

It was a blessed relief to hear the quietly passionate oration of organic farmer Don Bustos as he stood upon the land for 20 minutes to speak amid shifting rays of softening sunlight on an early August evening in Santa Fe, New Mexico. With dignity, he stood for clean food, for community food, and for food sovereignty.

Earlier on this crossquarter day the outpouring of farm news had been grim. We learned that the Dead Zone in the Gulf of Mexico caused by fertilizer and chemical runoff from industrial farming has swollen to an area larger than the state of New Jersey. We learned that despite scientific warnings the EPA declined to ban chlorpyrifos, a highly toxic farm pesticide known to interfere with human hormones, and to diminish IQ in children. We learned of serious labor shortages in the farm fields as immigration officials drive farm workers away from US lands. We learned that dramatic changes for industrial agriculture are essential now to reckon with the intensifying impact of climate change. We learned also that the suicide rate among US farmers is higher than that of the overall US workforce.

Without referencing any of these specific news items, Bustos acknowledged the larger system of which these developments are part. He mentioned the corporate industrial “militarization” of agriculture. Then with clarity and conviction he said that’s not the way to go. “We must grow food with respect. We must grow it in a way that acknowledges Creator and the spirit in the land.”

Bustos talk was part of the Farms Films Food program hosted by the Santa Fe Farmers Market Institute in collaboration with the Center for Contemporary Arts and the Street Food Institute.

The acequia-watered Santa Cruz Farm in Española, New Mexico that Bustos now tends has been in his family since the 1600s. Speaking broadly to encompass all of agriculture, he said that his big goal is “to make it possible that our children can farm on the land for the next 400 years.”

Nowadays Bustos cultivates about 70 crops on 3 ½ acres. At that scale, he’s developed an economic approach that enables him to give attention to the wider world. He trains young people to work the land, and to keep alive the centuries-old traditions of family farming in New Mexico. He’s a champion for community food sovereignty and for food justice at local, state and national levels. In 2015 he received the James Beard Foundation Leadership Award, specifically honored for his work “in support of farmers’ rights and education, and his efforts to include farmers of color in the national food movement.”

When he spoke in Santa Fe this week Bustos said that in his farming he’s guided by three keys: the traditional rituals and practices of northern New Mexico farmers, modern organic cultivation practices, and the Biodynamic Calendar.

“The strongest connection with Creator comes,” he said, “when you have your hands, feet and knees on the soil, and you are working with plants.” “Nature will tell you. You will understand signs so that you know you are on the right path.”

“I still grow and save seeds from our crops to plant the next year,” he said. “Saving open-pollinated, heirloom seeds is really important, but it’s not a silver bullet to solve the problems of agriculture.”

“Food should be grown in healthy soil with healthy water by people who are healthy. Then you have right relationship to the earth. The silver bullet is for everyone to take responsibility for their food by growing it, or supporting the people in their community who grow it for them. That connection to the Earth,” Bustos emphasized, “is important for everyone. It’s one of the Pillars of Food Sovereignty.”

EVERYTHING AT HAND – Massive, impressive cast-iron sculptures by Tom Joyce are on display until Dec. 31 at the Center for Contemporary Arts, site of the Farms Films Food program. (author photo)

Our community circle existed in time for just 91 minutes during Tierra Viva (Farming the Living Earth), the hemisphere-wide conference that was summoned into being by the

Our community circle existed in time for just 91 minutes during Tierra Viva (Farming the Living Earth), the hemisphere-wide conference that was summoned into being by the  practical and spiritual benefits arise for participants in CSA farming. CSA puts shareholders in greater tune with nature. This instinctual impulse to connect with the earth that sustains us is inherent in healthy people; consequently farming and gardening are healing and stabilizing for human beings, and of critical importance as we continue to face extreme and intensifying conditions in our digital era. Biodynamic principles and practices support and enhance all of this.

practical and spiritual benefits arise for participants in CSA farming. CSA puts shareholders in greater tune with nature. This instinctual impulse to connect with the earth that sustains us is inherent in healthy people; consequently farming and gardening are healing and stabilizing for human beings, and of critical importance as we continue to face extreme and intensifying conditions in our digital era. Biodynamic principles and practices support and enhance all of this. “core groups” to create a strong and reliable network of farm support, similar to the way volunteer Boards of Directors serve food coops. While the CSA core group concept hasn’t been popular in CSAs in recent years, it does “take a village” to make a CSA work at the highest possible level. Considering the radically changing circumstances in climate, politics and economics, the core group model – drawing on collective intelligence and resources – is well worth re-considering.

“core groups” to create a strong and reliable network of farm support, similar to the way volunteer Boards of Directors serve food coops. While the CSA core group concept hasn’t been popular in CSAs in recent years, it does “take a village” to make a CSA work at the highest possible level. Considering the radically changing circumstances in climate, politics and economics, the core group model – drawing on collective intelligence and resources – is well worth re-considering. community awareness of environmental issues. CSAs connect people to the earth viscerally. Through that connection people become more firmly rooted in the places where they live and in the natural world, which supports life. Food is a binding impulse that can transcend political orientation. Food is an effective way to invite people into a real community conversation, and to combine their skills and resources to become more effectively and skillfully resilient in the face of the great challenges.

community awareness of environmental issues. CSAs connect people to the earth viscerally. Through that connection people become more firmly rooted in the places where they live and in the natural world, which supports life. Food is a binding impulse that can transcend political orientation. Food is an effective way to invite people into a real community conversation, and to combine their skills and resources to become more effectively and skillfully resilient in the face of the great challenges. mmunities often awaken late because of direct crisis, but they can also awaken from intelligent pursuit of models and opportunities. Dialogue can be a big factor in this; thus, it’s important to continue to articulate not just the economic and health dimensions of CSA farms, but also the social and ecological benefits.

mmunities often awaken late because of direct crisis, but they can also awaken from intelligent pursuit of models and opportunities. Dialogue can be a big factor in this; thus, it’s important to continue to articulate not just the economic and health dimensions of CSA farms, but also the social and ecological benefits.

Our era is sharply marked by the mounting, menacing clouds of climate chaos, paralleled by dramatic and urgent shifts in global politics, economics, and social relations. Much more than a market strategy is required. I remain steadfast in my conviction that CSA can play a key role in addressing these issues. It’s time to expand exponentially the CSA vision and reality to hundreds of thousands of community farms around the world, and time also to evolve consciously the community and the associative economic dimensions of CSA.

Our era is sharply marked by the mounting, menacing clouds of climate chaos, paralleled by dramatic and urgent shifts in global politics, economics, and social relations. Much more than a market strategy is required. I remain steadfast in my conviction that CSA can play a key role in addressing these issues. It’s time to expand exponentially the CSA vision and reality to hundreds of thousands of community farms around the world, and time also to evolve consciously the community and the associative economic dimensions of CSA. A rootstock is part of a plant, often an underground part, from which new above-ground growth can be produced. Grafting refers to the process by which a plant, sometimes just a stump with an established root system, serves as the base onto which cuttings (scions) from another plant are joined.

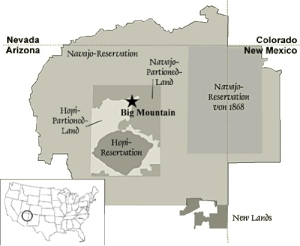

A rootstock is part of a plant, often an underground part, from which new above-ground growth can be produced. Grafting refers to the process by which a plant, sometimes just a stump with an established root system, serves as the base onto which cuttings (scions) from another plant are joined. Is there, or could there be, a biodynamic preparation that aids, nurtures and supports the grafting of the world’s wide array of cultural and agricultural traditions to the native rootstock and wisdom ways so inseparably a part of North America?

Is there, or could there be, a biodynamic preparation that aids, nurtures and supports the grafting of the world’s wide array of cultural and agricultural traditions to the native rootstock and wisdom ways so inseparably a part of North America?

Climate distortion has been speeding up

Climate distortion has been speeding up